Any Legume Tofu

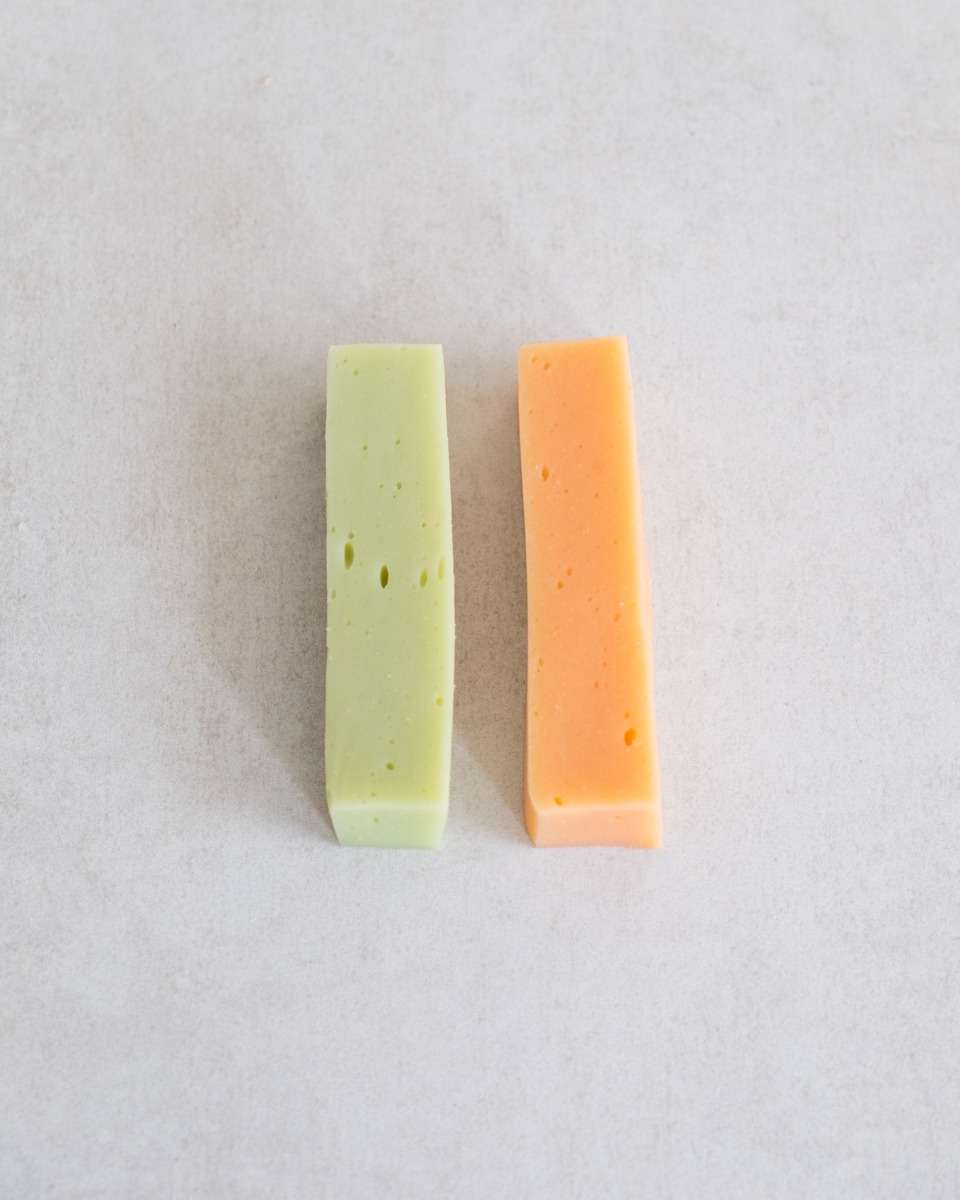

Burmese tofu is a common dish from the Shan minority in Burma (Myanmar) that is traditionally made with flour from split yellow lentils or chickpeas. It is different to traditional Chinese tofu, which is made by curdling soy milk and pressing the curds into a firm block. Instead, with Burmese tofu, the liquid is heated until it begins to coagulate and is then left to set into a soft block. Because of the difference in texture, you can’t use Burmese tofu as a substitute for firm soybean tofu, as it is rather delicate and might not withstand much stir frying or longer cooking times in liquids. I prefer cutting Burmese tofu into cubes and shallow frying them with a bit of salt until golden brown on each side. They can then be coated in your favourite sauce or spices and used to top off dishes or served as a side.

Although Burmese tofu is commonly made with chickpea flour, you can, in essence, use any dried legume and apply the same method by soaking and blending them. Most legumes are high in protein (around 20%). By extracting and heating them, you can change the protein bonds, causing them to firm up. Most of us have already experienced this process before when boiling an egg, turning the white from translucent to firm. Although this works with any dried legume (peas, lentils, beans…), it’s slightly different with soybeans, which are even higher in protein (around 40%) and therefore begin to curdle when heated in the form of soy milk like in this recipe.

IMPORTANT: Raw legumes, especially certain beans, are not safe to consume, because they contain natural toxins as a defence mechanism against predators. By straining the blended legumes, you’re removing any larger particles that might not cook in time, so please don’t skip this step or the tofu might upset your stomach. Always make sure that your tofu has set properly, otherwise start over instead of eating it anyway. If you’re concerned about waste and want to use the leftover pulp in the tofu as well, you can follow the tip at the bottom of the recipe.

Ingredients

-

200g dried legumes (chickpeas, beans, lentils)

Method

Soak the legumes in plenty of water overnight or for at least 8 hours.

The next day, drain the legumes and pulse them in a food processor (I use Ninja) to break down slightly. Then add 500 ml of water and blend until smooth.

Filter the blended legumes through a sieve into a sauce pan and use the back of the spoon to squeeze out as much liquid as possible (You can discard the leftover pulp, or use it to thicken stews, soups or even mix it into breads like this Sourdough Rye). Add 1/2 tsp of salt to the liquid and whisk it in. You will notice that some of the protein has already sunk to the bottom of the pan. Make sure to loosen it with the whisk or it will burn.

Bring the liquid to a gentle boil, whisking constantly. Keep simmering for 1 minute, whisking every now and then, until the mixture sticks to the whisk and doesn’t instantly level out when you stir it. When you tilt the pan, the liquid should move slowly. If it feels too runny, just cook it a little longer. Once ready, pour the mixture into a mould and let it set for an hour before using.

**I receive a small commission from affiliate links on this page**

Any Legume Tofu

Ingredients

- 200 g dried legumes (chickpeas, beans, lentils)

Instructions

- IMPORTANT: Raw legumes, especially certain beans, are not safe to consume, because they contain natural toxins as a defence mechanism against predators. By straining the blended legumes, you’re removing any larger particles that might not cook in time, so please don’t skip this step or the tofu might upset your stomach. Always make sure that your tofu has set properly, otherwise start over instead of eating it anyway. If you’re concerned about waste and want to use the leftover pulp in the tofu as well, you can follow the tip at the bottom of the recipe.

- Soak the legumes in plenty of water overnight or for at least 8 hours.

- The next day, drain the legumes and pulse them in a food processor (I use Ninja) to break down slightly. Then add 500 ml of water and blend until smooth.

- Filter the blended legumes through a sieve into a sauce pan and use the back of the spoon to squeeze out as much liquid as possible (You can discard the leftover pulp, or use it to thicken stews, soups or even mix it into breads like this Sourdough Rye). Add 1/2 tsp of salt to the liquid and whisk it in. You will notice that some of the protein has already sunk to the bottom of the pan. Make sure to loosen it with the whisk or it will burn.

- Bring the liquid to a gentle boil, whisking constantly. Keep simmering for 1 minute, whisking every now and then, until the mixture sticks to the whisk and doesn’t instantly level out when you stir it. When you tilt the pan, the liquid should move slowly. If it feels too runny, just cook it a little longer. Once ready, pour the mixture into a mold and let it set for an hour before using.

hi Hermann, have a quick question if you may have time to respond. Usually lentils or any other legume must be cooked thoroughly in average 20-30 min (either boiled or baked). All this trend with legumes tofu recipes calls for blending with water and quickly cook this mix for max 10 min then put it into mold. I really dont understand how this mixture can be considered ready-to-eat as its obviously raw and not cooked enough?… plus the taste which is bad for raw legumes…whats your take on this very important fact?

thanks alot in advance

Hi Marcela, you’re absolutely right, raw legumes aren’t safe to eat. I write about this in the recipe introduction as well as during the method. Have you already read through the full page? It explains it in more detail. When it comes to this recipe, by straining the blended legumes you’re removing the particles that wouldn’t cook in time, allowing you to turn the liquid into a tofu. If you follow the method without straining, you need to be more careful which legumes you’re using, since some contain more toxins than others. Soaking overnight also helps to break down some of the toxins. Please refer to the introduction and method, though 🙂

I just made a big batch of this, it’s my first time trying. This was a lot of fun to do as well! I discarded the pulp for my first time (as much as it pains me to do so, but I didn’t want to tackle too much at once on a new recipe). Should I press this tofu at all? And do you have the nutrition facts for the lentils since the lack of pulp I assume changes some nutritional value?

Fantastic! No need to press the tofu. You only press curdled “milks”, like soy milk, in order to bind the solids and get rid of as much moisture as possible. This tofu is a bit different, because it’s coagulated rather than curdled. I’m not sure about the nutritional values, unfortunately, but you’re right, removing the pulp will certainly impact it. If you can be bothered, you can use the pulp in other recipes though. I quite like to plan it in a way that I can add it to soups/stews that I serve alongside the tofu. Or even use it in breads.

Just tried to make my first batch and I’m sure it’s my execution and not the recipe but it was very soft, weak and fell apart easily. I let it boil to the point as described but I think I should have left it a bit longer.

I also didn’t have any decent shallow moulds handy so used a silicone bread tin, so quite deep, which may have affected the water evaporation quite a bit despite me leaving it several hours.

Needless to say it’s been a fun process and I’m experimenting with different ways to get the correct texture but it didn’t look anything like the examples… yet! I’ll get there 🙂

Thanks for giving it a go! Such a shame that it came out too soft. The texture is different to soy-based tofu, so it’ll never be quite as firm. But you’re right, to get it a little firmer, just cook the paste for longer. Next time, cook it to a point where it won’t level out at all anymore by itself when you pour it into the mould.

To avoid the need to cook beans longer to get rid of the toxins, can you use canned beans and the no-waste method?

Unfortunately not. They have been pre-cooked and won’t have the same qualities needed to coagulate the liquid.

Hi ! Thanks a lot for your recipes 🙂

It feels amazing so I tried it exactly the same but at the stage of cooking my firm cubes of tofu (I used lentils), as they heated in oil, they loosen and I ended with a paste. The cube wouldn’t stay firm. Yet I tried to really be carefoul at the stage of firming the paste in the pan as you did in the video but maybe I did not enough. Do you have a suggestion ?

Hm, I’m sorry about that! Yes, try cooking the paste a little longer next time. That will get rid of more moisture and make a firmer tofu. It’s also best to use a non-stick pan and give the tofu enough time to build a crust before trying to turn it gently. Keep in mind that this kind of tofu will never be as firm as soybean tofu, so it’ll still have a somewhat creamy texture.